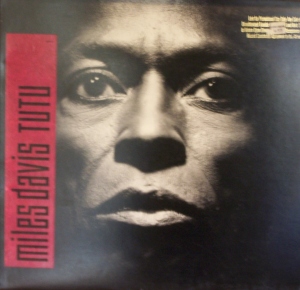

The jazz group Mostly Other People Do The Killing is recording Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, and The Jazz Times asked: “What’s Your Take?”

My take? Why bother? If you want to hear Kind of Blue, there’s plenty of ways to hear Miles Davis and his group do it.

I don’t get the point of cover bands or tributes. They’re music’s version of decaffeinated coffee or non-alcoholic beer. The real thing is better and has the intended impact.

Good for MOPDK if they want to play Kind of Blue, and good for the group for bringing attention to the album. But why settle for a copy when you can get the original?

Said Quincy Jones, according to Ashley Kahn’s book on the album, Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece: “I play Kind of Blue every day—it’s my orange juice. It still sounds like it was made yesterday.”

You think Jones wants some artificial orange drink instead? Kind of Blue is 55 years old. If Quincy Jones hears the copy rather than Miles, he’ll be likely to spit out whatever he’s drinking as if it was 55 years old.

It may be that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. And that the album is meant as tribute. But if they copy it note for absolute note, timed to the tenth of a second, it’s no more jazz than Kenny G. Doesn’t that miss the point of the music?

I’m not sure how Miles would feel about it, whether he’d be flattered or slighted.

My guess? He’d turn his back on it.

That’s good enough for me.

The link above is to All Blues, song one on side two of the album. From allmusic.com: “‘All Blues’ was a live staple throughout much of Davis’ career, and it’s easy to see why – the tune is built upon the melodic brilliance of Davis’ trumpet, which even Coltrane fails to upstage during his solo. ‘All Blues’ is also a testament to Jimmy Cobb’s light, fluid drumming, a rather unsung hero of the Kind of Blue sessions, but a most vital member of the group.”